How The Fear Of Failure Can Make You Take Draws In Better Positions

And why it's better to cultivate the habit of playing on instead

Do you find the fear of losing or making mistakes crippling?

Losing, especially, can be painful when you expected to win or you became attached to the idea of winning. When you lose a game you were winning, the memory of it can linger for a long time, and because of the result, you might feel like you’ve failed.

Happiness = Reality - Expectations

Once you’ve internalised a chronic fear of failure, you might go out of your way to altogether eliminate the risk of failing.

Fear is a message—sometimes helpful, sometimes not—but often conveying critical information about our beliefs, our needs, and our relationship to the world around us.

—Harriet Lerner, The Dance of Fear

The fear of failure can be worse than failure itself, because while losing and making mistakes are inevitable parts of the game, the fear of failure can make you risk-averse and not able to enjoy playing any more.

Here’s an example: one of the games I regret the most in recent years.

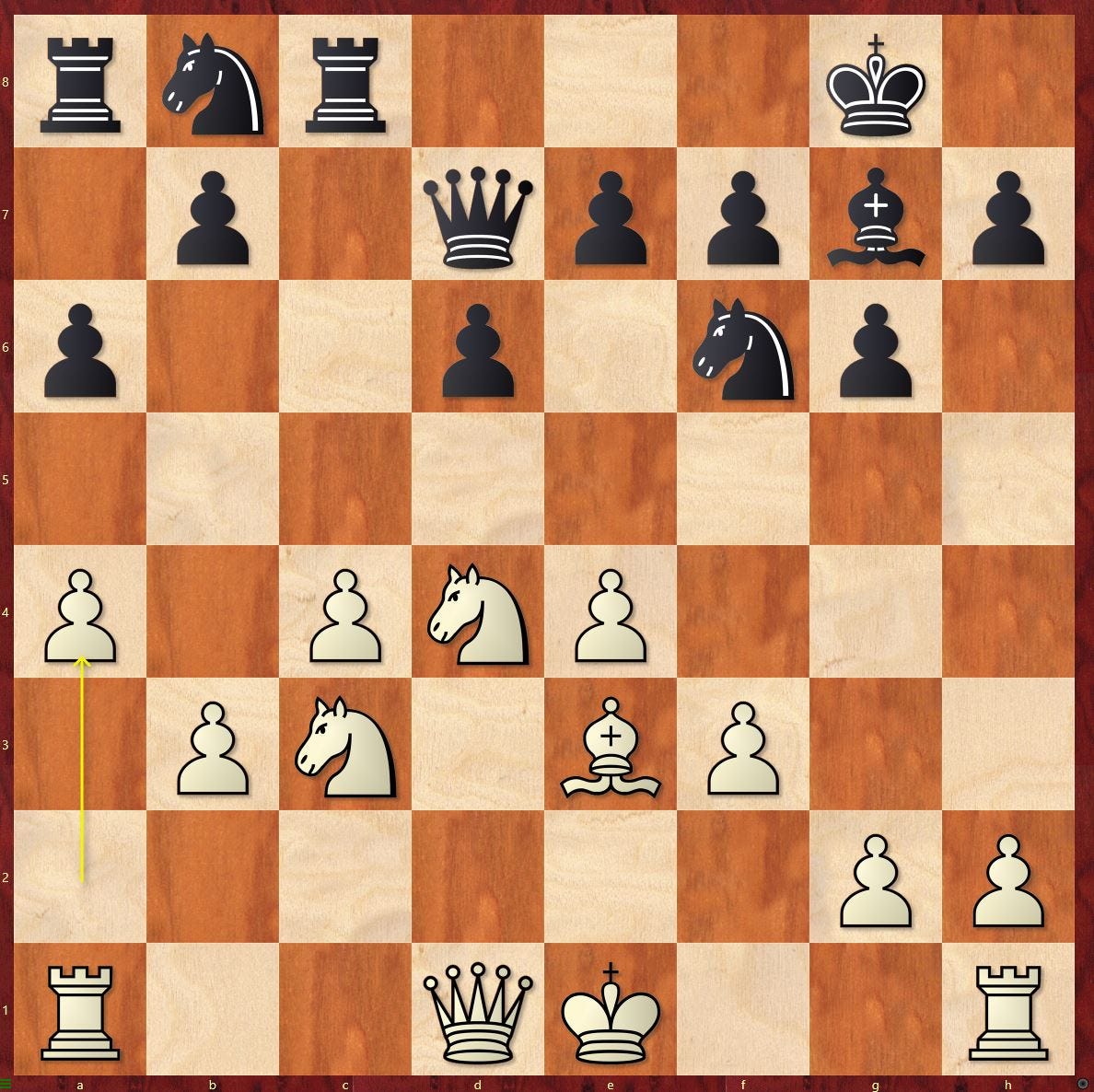

Ikeda (2457)–Zhao (2525), Begonia Open (4.2), 13.03.2022

1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. Bb5+ Bd7 4. Bxd7+ Qxd7 5. c4 Nf6 6. Nc3 g6 7. d4 cxd4 8. Nxd4 Bg7 9. f3 O-O 10. Be3 Rc8 11. b3 a6 12. a4 (12. Rc1 is recommended by So in his Chessable course on 1.e4)

12...e6 13. Rc1 d5 14. e5 Ne8 15. cxd5 exd5 Here my opponent offered a draw. A quick draw as Black against a slightly lower-rated player was a good deal for him, with one more game to play in the evening.

I’m ashamed to say that after thinking for some time, I accepted.

After 16.f4 and castles, White is the one pushing for an edge, with Black having a weakness on d5 and pieces struggling for space.

I really regret this decision, even 13 months later, most of all because I was curious about how the game would continue. We’d just entered an interesting middlegame. White is not even in any risk (though, of course, as an overthinker, the more I thought, the more apparent dangers there usually are, too).

So why did I accept?

The excuses I was cooking up in my mind were that (picture a cockatoo saying these)

I’d been away from the board for 8 months prior to this tournament, and I felt like my mind wasn’t working well at all during this tournament;

I wasn’t in the best physical shape, still recovering my stamina levels from a shoulder surgery a few months ago;

I was already exhausted, and wanted to minimise further fatigue from the second of three games of 90+30 I’d be playing that day;

…but ultimately, I was just scared. Scared of playing on, scared of doing my best and losing, scared that I wasn’t good enough. I decided to play it safe, and chickened out of playing a game against a stronger player I would have learnt from, whatever the result.

By not trying, they always have an alibi: “I may have lost, but it doesn’t count because I really didn’t try.” What is not usually admitted is the belief that if they had really tried and lost, then yes, that would count. Such a loss would be a measure of their worth…based on the mistaken assumption that one’s sense of self-respect rides on how well he performs in relation to others…fear of not measuring up.

—Timothy Gallwey, The Inner Game of Tennis

I often see young, promising players taking draws in advantageous positions against stronger opposition, being content with a ‘good result’ or gaining some rating.

As with the game above, I haven’t been immune to taking ‘the easy way out.’

But I can say from experience, of mine and others through my chess life, that taking premature draws when the game is still interesting, especially when you are holding the advantage, invites regret most of the time. Alternatively, if you don’t regret it, you may not have realised the opportunity you missed by not playing on.

At the time, you think that the draw is not a bad thing by any means, perhaps saving your struggles and real tests for future games. That by accepting or acquiescing to a draw against a higher rated player, you’ve passed ‘this test’. You assume, especially if you’re a younger player, that you’ll continue improving as you play more, and thus gaining rating from the draw allows you to ‘improve’ faster. The reality is the opposite.

In the long run, you’ll improve more if you make it somewhat of a rule to play on in these promising positions because you learn from the experience. You’ll lose some, perhaps even many of these games, but the lessons you learn as you give your best will teach you invaluable lessons you’d miss out on if you chicken out.

What better way is there to improve your game than battling it out against stronger players over the board?

Another reason stronger players manage to escape in worse positions by offering a draw is that their opponent gives them a lot of respect. ‘If my strong opponent is content with a draw, is it really worth pushing and taking a risk when it might be futile?’ Accepting the draw and drawing after playing the game out result in the same score on the table, but the experience and wisdom gained are invaluable. The stronger opponent is offering a draw now because they’re worried they might lose.

Later, I began to succeed in decisive games, perhaps because I realised a very simple truth: not only was I worried, but also my opponent.

—Mikhail Tal, The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal

The action of spurning the easy way out, and making a habit of it, gives you that fire of self-belief that grows over time. Ultimately, you want to play chess to become a better player, rather than increase your rating. The two are connected, but while the latter tends to follows the former, the former doesn’t necessarily follow the latter.

You might increase your rating in the short term, accepting draws—and you might still become a better player—but you’ll learn the most by playing on, even if you’re scared of failure. In the end, when our life and chess lives are both finite, why not live out more of your ‘lives’ over the 64 squares, to the fullest?

For the fact is that there is no humiliation so great that one should not accept it with unconcern, knowing that at the end of a few years our misdeeds will be no more than an invisible dust buried beneath the smiling and blooming peace of nature.

—Marcel Proust, Time Regained (In Search of Lost Time #6)

Other posts relating to draw offers in chess

Why You Should Reject Draw Offers (GM Hovhannes Gabuzyan on ChessMood)

Why You Should Never Offer A Draw (GM Noël Studer on Next Level Chess)

This post really resonates with me. Definitely accepted and offered way too many draws in my youth.

I think it's also really hard when you're so young to have this perspective of long-term vs short-term gains (I think I've only just started to appreciate this in the last year or so) - especially without some sort of coach.

Nice post. It's a big thing, the psychological element. It's why I predict Nepo will have a very hard time if he loses two in a row. (I am a clinical psychologist by profession, not that this gives me any authority on predicting the outcome of world championship chess matches). Also, the Proust is noted. Everything goes to dust, indeed.

On the diagram front, admittedly I'm not super techie, but all I was able to do was embed a gif of a lichess study chapter. The other approaches failed. Granted, I devoted all of 5 minutes to this. Perhaps I can put the gif here?

https://lichess.org/study/pddtrB6v/DVF0hXKy.gif?theme=brown&piece=alpha