Many of your games are decided in 'critical moments’.

These are positions where the cost of your next move is high.

the decision might decide the result of the game

the position requires deeper calculation/thinking than on other moves.

Let’s look at two examples.

Example 1

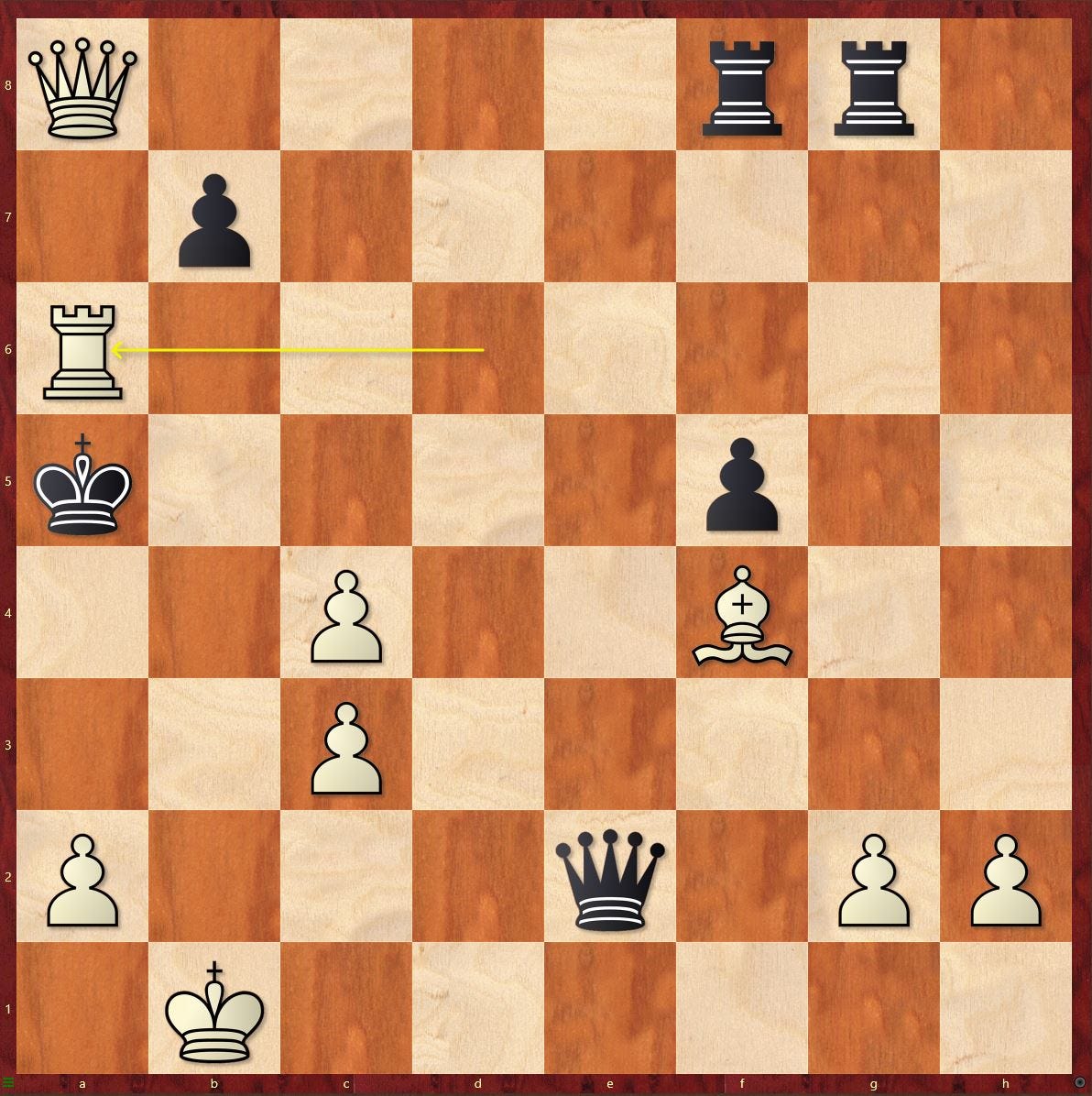

Ding Liren (2788)–Ian Nepomniachtchi (2795), WC match (Game 8), 20.04.23

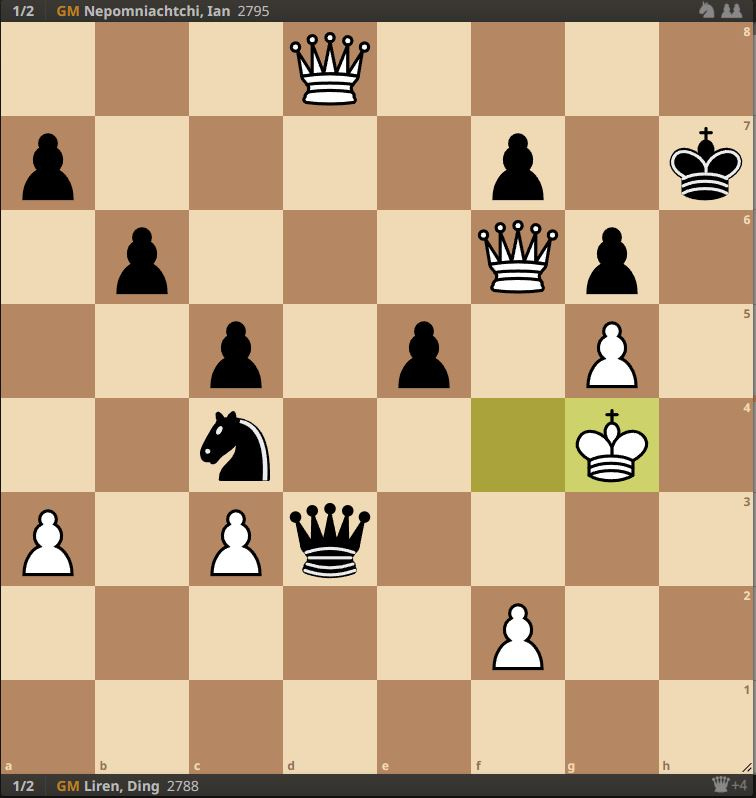

You might remember this one. In the diagram below, Nepo spent 3 minutes before playing 31…Qh4. The players each had around 25 minutes left here to make all of their moves until move 40, when 60 minutes would be added for the next 20 moves.

Ding spent less than 3 minutes to respond with 32.Kd1.

Amazingly, he could have taken the rook with 32.Qxd8 and avoid the seemingly unavoidable perpetual check after 32…Qe4+, with the longest variation going 33.Re2 Qb1+ 34.Kd2 Qb2+ 35.Kd3 Qb1+ 36.Rc2 Qd1+ 37.Ke4! Qxc2+ 38.Bd3 Nd6+ 39.Ke5 Qxd3 40.Qf6+ Kh7 41.d8=Q Nxc4+ 42.Kf4 e5+ 43.Kg4 (D). The king will reach safety soon.

A difficult line, but one these two would have managed to calculate. In the press conference Ding explained, “I briefly checked this line but I stopped. I saw 35…Qb1+ 36.Rc2 [Qd1+] and didn’t calculate any further. I didn’t have much time and considering yesterday’s loss, I wanted to play quickly to avoid time trouble.”

It’s easy to criticise him when you know White could take the rook and win. What if he had spent more time and it turned out Black can draw after all? It’s a tough call during a game, deciding whether to calculate. Ding obviously has a world-class eye for critical moments, but this example shows how practicality can (and often should) take precedence over expending valuable time [you can play through the game here].

Example 2

Ikeda (2387)–Leong (1713), Darling Downs Open (3.1), 13.05.23

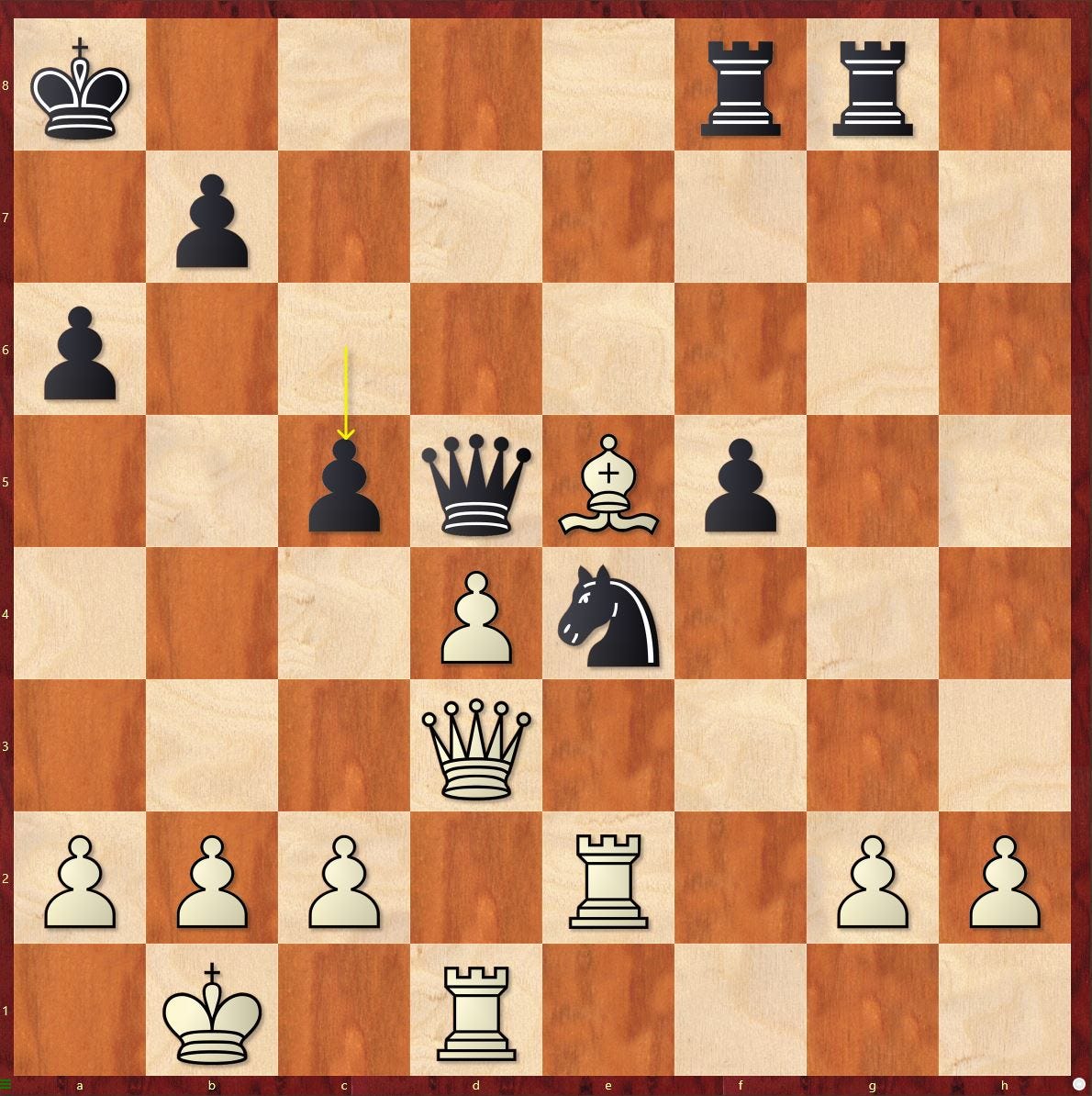

Black’s just played 27…c5 in this position where I’m a clear two pawns up.

Here, with around 18 minutes left (this game was played with 60 minutes+10 seconds/move), I sensed this was a critical moment. I became fixated on 28.c4 Qe6 29.Bf4, especially …cxd4 30.Qxd4 Nc3+ 31.bxc3 Qxe2 32.Be3 which I thought should be winning, but with the minutes ticking down, I couldn’t find a win after 32…Kb8 (D).

Down to a few minutes without finding a solution, and annoyed at myself for thinking for so long, I played the cautious and not-very-strong 28.b3 instead.

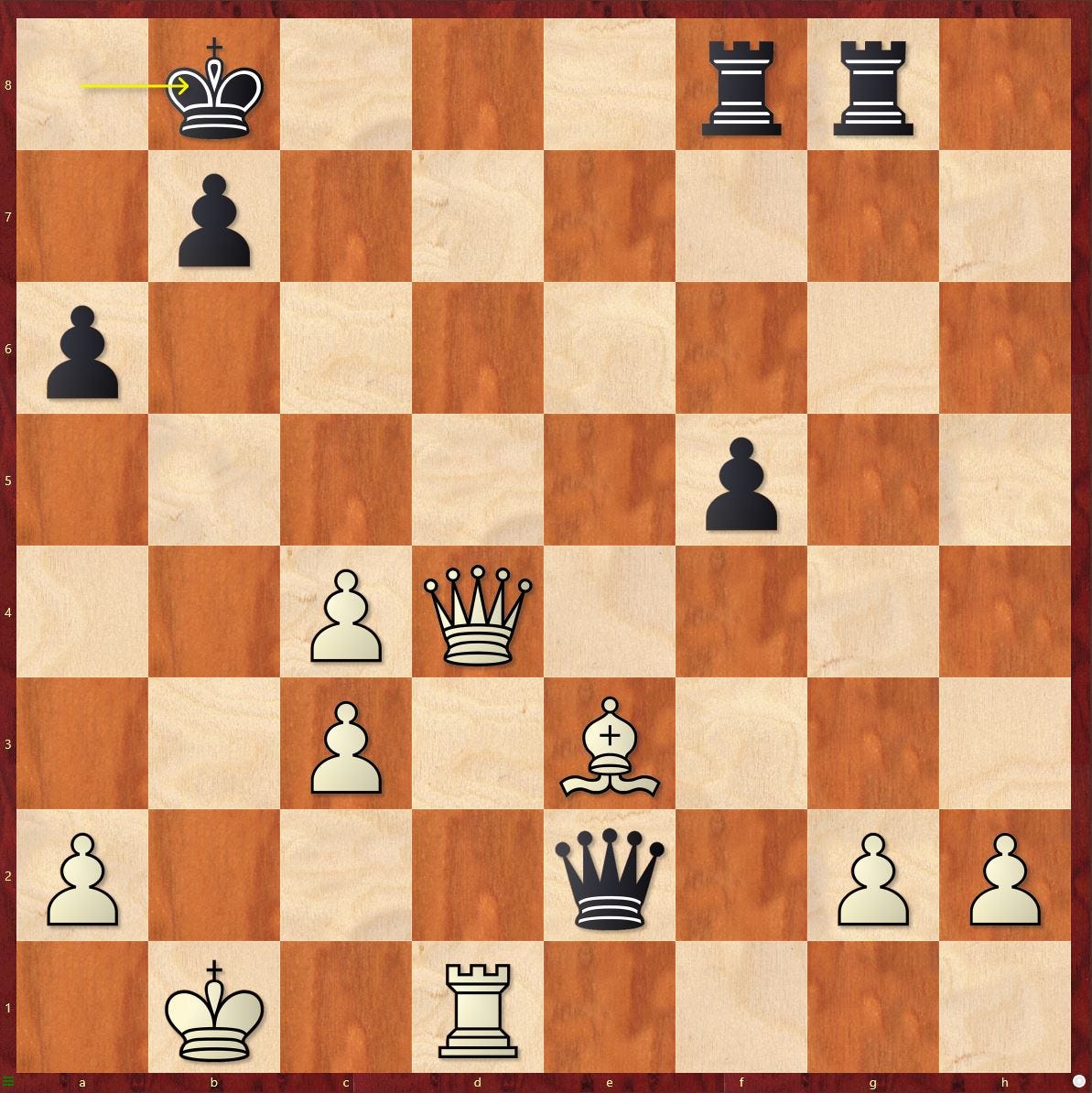

I made it to a winning queen endgame, but my nerves had taken a hit in time trouble, leading to playing 53.b4 (D) completely forgetting about protecting the h-pawn!

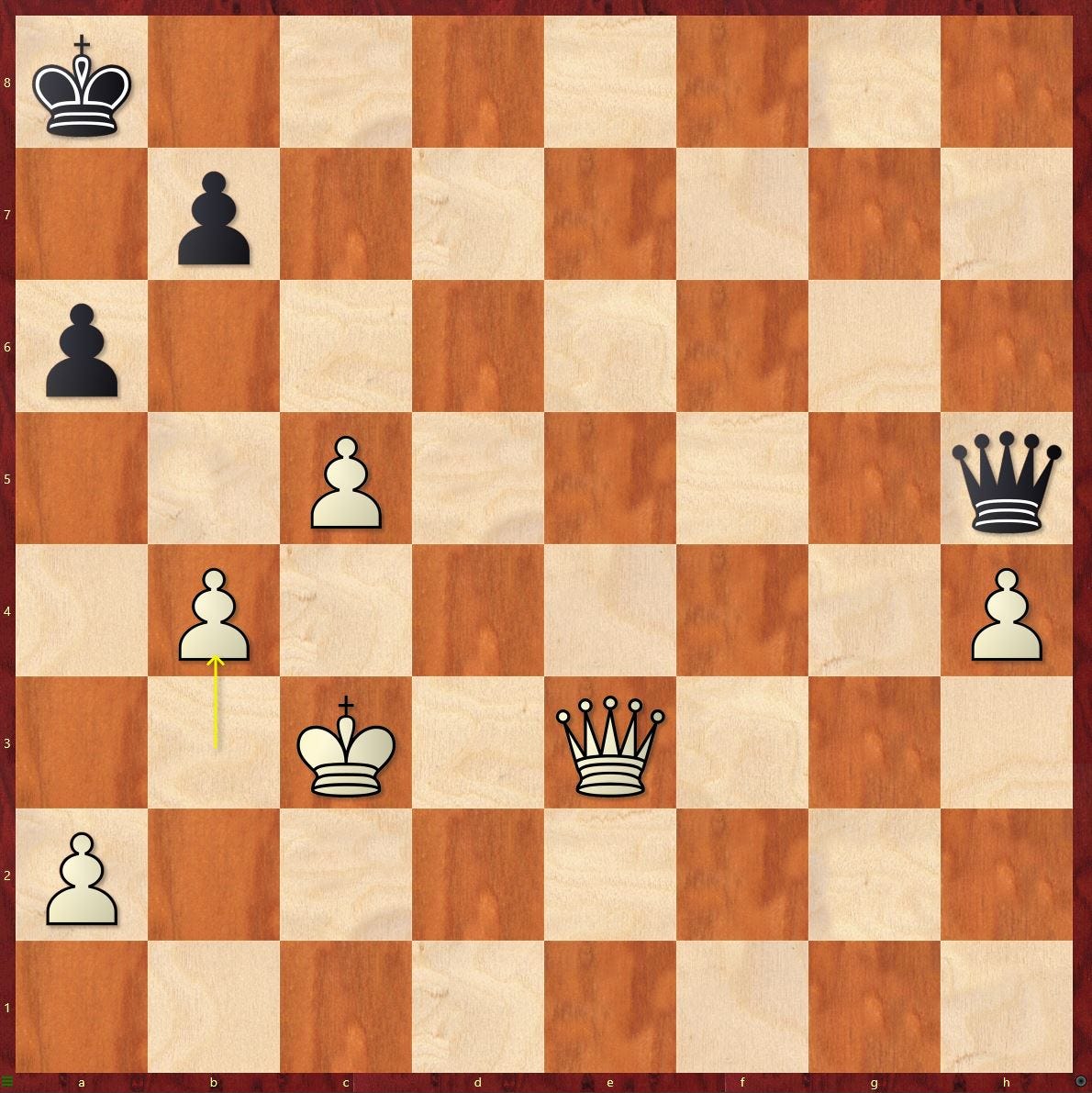

Spending most of my remaining 18 minutes on 28.c4 was dumb and impractical. It turns out White does have a win after 32…Kb8, e.g. with 33.Qa7+ Kc8 34.Qa8+ Kc7 35.Bf4+ Kb6 36.Rd6+ Ka5 37.Rxa6+! (D) followed by mate, but that’s not the point.

Unlike the Ding–Nepo example, the opponent wasn’t forced to go into this variation at all if I’d played 28.c4. Not only that, 28.c4 is not bad, but not a game-changing move, so I totally misjudged the position in thinking it was a critical moment. Since I was a healthy two pawns up, I should have focused on playing healthy moves while avoiding time trouble, as Ding did [the game is available here].

The post-mortem of (potential) critical moments

You can examine particular positions in games through these angles:

was it a critical moment?

did the player think it was a critical moment?

did they end up playing a good move?

was time a factor in the decision?

In Example 1, Ding’s game,

it was a critical moment

he didn’t think it was a critical moment

he ended up missing a clear win

time was a factor. Ding decided not to calculate further to save more time for later.

In Example 2, my game,

it wasn’t a critical moment

I thought it was a critical moment

I ended up playing a move which was relatively weak, but still retaining my edge

time should have been more of a factor. Since the opponent’s responses weren’t forced, it wasn’t practical to spend so much of my remaining time on those lines.

Try looking at moments in your games you thought were important through this lens.

Using the concept forwards rather than backwards

Analysing things in this way can give you some good feedback.

But what you want to know is how or if the concept of critical moments can help you during your games.

In a perfect world,

you’d be able to sense critical moments

you’d be able to deliberate on it and make the right choice

your handling of the clock would allow you to have plenty of time for these moments while also keeping enough time for your play afterwards.

But of course, each of these factors are not givens.

you might correctly sense a critical moment, but have no time to calculate

you might correctly sense a critical moment and have time to calculate, but fail to find anything

you might miss a critical moment and be in time trouble, but still play the best move anyway and win.

Because critical moments contain so many interrelated elements, and we all think at the board in different ways, it’s difficult to boil this concept down into a simple, actionable concept that works even some of the time. However, I do think thinking about your thinking is meaningful, and through the concept of critical moments, you can think about differences in the importance of positions in your chess.

if you’re always in time trouble, you might be failing to distinguish between when you should think, and when you should play without thinking too much

if you often blunder even when you have lots of time left, you might be failing to notice when it’s a critical moment that requires serious thought

if you sense critical moments but often go in the wrong direction because you neglect strategic considerations, you might rely too much on calculation.

Here are a couple of tips if you’re interested in exploring yourself:

when following a game live or playing through it afterwards where you can see the move times, put yourself in one of the player’s shoes and compare not just your moves with them, but also how much time you spent. A stronger player thinking more or less than you in different positions doesn’t mean they’re right, but you can learn about the differences with your model player by examining and comparing the moments where each of you spent the most time thinking. Stronger players tend to not only be better at calculating, but knowing when to.

the objective in most of the tactics people focus on solving in training are finding the best move or finding the forced win/draw (as quickly as possible). While this is useful, it’s useful to diversify the nature of positions you’re solving, not only in type of position but goal. On most of your moves during a game, there is no clear win or best move—in most positions, the most important skill you can have is playing healthy moves which doesn’t worsen your chances (more on this in another post!). Being able to go deep even in seemingly boring positions brings dividends.

It seems that events are larger than the moment in which they occur and cannot be entirely contained in it. Certainly they overflow into the future through the memory that we retain of them, but they demand a place also in the time that precedes them. One may say that we do not then see them as they are to be, but in memory are they not modified too?

—Marcel Proust, The Captive/The Fugitive (In Search of Lost Time #5–#6)

Junta, Great post as always! I don't know if its good new or bad news that you are hundreds of points stronger than me, but often highlight mistakes of yours of a similar nature to mine!