What changes affect players as they get older?

How can older players cope with these changes and thrive?

What choices can a player make at any stage of their career to help ‘future-proof’ their game?

GM Matthew Sadler and WIM Natasha Regan, perhaps more well-known for their book on AlphaZero, Game Changer (2019), set out to explore these questions and much more in their unique and charming work, Chess for Life (2016).

Each chapter focuses on one of the 13 ‘role models’—grandmasters who have played professionally (Cramling, Nunn, Judit Polgar, Speelman, Miles, Tiviakov, Short, Gaprindashvili, Seirawan, Arkell), other titled players (Terry Chapman, Ingrid Lauterbach) and Capablanca.

Ten were interviewed, mostly about their chess and chess life, and aspects of some of the players’ games were examined in great detail. Regan handled the data analysis while Sadler wrote about the chess.

Here are 5 things I loved in the book:

1. Deep analysis of players’ opening choices/philosophies

These were my favourite, and I would have been more than happy with the purchase of the book just to read these chapters on Miles, Tiviakov and Cramling.

"Tony Miles: The Rebel”

The authors examined players’ opening repertoires through different time periods, highlighting the changes they made to their repertoire over the years and how those changes worked out. You can’t conclude much from one game, but when you have hundreds of games over many years, you can find interesting and meaningful patterns.

Miles changed his main option against 1.e4 a few times through his career while dabbling with many sidelines, and played different lines based on his opponent.

As I avoided main lines until quite recently, I could sympathise with the kinds of problems he encountered through his career, and many of Sadler’s observations made me think about my last two years when I really got into openings.

And that is the downside of experience. Over the years your opening repertoire gets stretched by your experiences—you discover lines you’d rather not play, a line you used to like as a surprise weapon becomes popular and the theory moves too fast for you to keep up, a novelty puts one of your lines out of commission—and at some stage your repertoire no longer works as a whole any more.

“Sergey Tiviakov: Always Building”

An ideal approach to openings would be to have one main opening and build up expertise within it over time. Typical concerns against this approach would be:

Predictability—If you always play the same opening then you’re easier to prepare for. It’s an uncomfortable thought knowing that opponents are ready for you, armed to the teeth with computer analysis.

Opponents of differing strengths—Can you really play the same opening both against strong players you want to draw against and against weaker players you want to beat?

Sadler answers that you can, but you need to be aware of all the possibilities. Tiviakov is a great role model here. The former 2700-rated GM decided in 2005 that he needed to change his approach to chess, and switched from main lines to sidelines. Chess for Life takes a deep dive into his pet system, the Scandinavian with 1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qd6—and it was fascinating to observe how he managed to build so many weapons into this system, various mix-up options at every move, all grounded in deep knowledge of the middlegame and win condition/strategies. Even if you know he is playing this system, preparing effectively against it is an incredibly difficult task!

“Pia Cramling: Cool and Consistent”

Cramling switched to 1.d4 type openings around 1985, and she has been performing excellently with it for 30 years without needing any major overhauls. As someone who also switched from 1.e4 to 1.d4 last year, the comprehensive comparison between

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 vs. 3.Nc3 and

Nf3 systems vs. Nc3 systems, from both the chess and practical points of view

was very illuminating, as were the ways in which Cramling maintained and refined a main line repertoire while also scoring excellently with side lines and surprise lines.

A valuable chapter for 1.d4 players and those considering switching to 1.d4!

2. Chess through the life course

Are there any other books that look at how one’s chess and relationship with chess changes over time? This should be a fascinating topic for many adult players.

Here’s a brief outline of my chess life:

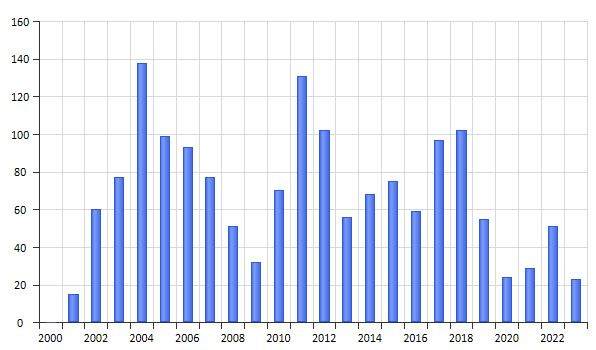

I learnt chess when I was 6, back in 1998.

Chess was probably the biggest thing in life through school and most of my 20s.

I started working full-time in late 2018, resulting in less games since:

I became an IM in 2014, scored a GM norm in 2017 and reached a FIDE high of 2460 in 2022. After a couple of horrible performances in October 2022 and April 2023 I’m back below 2400 but I’m optimistic for what the future holds.

My relationship with chess is the healthiest now—when younger, I was playing a lot but not training with discipline, and bad results would feel crushing. I’m not able to play as much now but I’m spending more time on chess in a conscious manner, and I know it’s not the end of the world even if games don’t go my way.

The ‘role models’ in the book, many of them who played professionally, gave heart-warming interviews on how their relationship with chess changed over time.

When you get a little older, you realise that losing a game or not qualifying, it’s not that important. Also for me becoming a mother, you become more responsible, and chess is something wonderful but it doesn’t end the world. Yes, I’m more relaxed now.

—GM Pia Cramling

What’s changed in your chess life as you got older? I’d love to hear some stories from readers of this Substack—let me know in the comments.

3. Eye-opening insights

From openings to playing style, philosophies to practical tips, Regan’s data analysis and Sadler’s observations combine to deliver a book that’s sure to provide some fresh perspective that could be useful for your chess.

I started to experiment with a standard check at the end of my thinking process where I imagine the positions I’ve been analysing with the queens off. I found it was an extremely useful visualisation technique.

Opening study can cost both amateurs and professionals an immense amount of effort. Amateurs will want to ensure that their effort in learning openings will stand them in good stead not just for the immediate game or tournament but over a longer time. We have called this the ‘longevity’ of an opening for a player, characterised by:

the likelihood that the opening will not be refuted in the near future

the flexibility of the opening—giving the player reasonable options to vary according to circumstance

the ability for that player to remember the ideas of the opening.

4. Tips for improving

The role models were asked for tips they could give to players aspiring to improve. Here are a few of them that were mentioned in multiple interviews:

get pleasure out of chess.

find a style you love and stick with it.

don’t focus on openings unless you really enjoy studying them.

you need to put in a huge amount of time on chess and put in a lot of work.

5. Love for chess

When I found chess, I really found myself. It really suits me as a person.

—GM Pia Cramling

I’ve read many chess books, and some of the key elements for me are

how instructive is the book?

how entertaining is the book?

are the authors passionate about the subject matter?

I didn’t rate the book higher because I found a few of the chapters weren’t as interesting as the rest, but this book was a pleasant surprise for me. It ticked all three boxes above, and most of all, it’s obvious from every page how much Sadler and Regan love chess and are happy to be sharing all of their findings and observations with you.

A book I would recommend especially to

adult improvers

fans of some of the role models

those who have returned to chess after a break

chess enthusiasts who enjoy detailed player analyses.

Book page on the Gambit Publications website

Throughout our childhood and teenage years we strive to attain the correct distance from objects and phenomena. We read, we learn, we experience, we make adjustments. Then one day we reach the point where all the necessary distances have been set, all the necessary systems have been put in place. That is when time begins to pick up speed. It no longer meets any obstacles, everything is set, time races through our lives, the days pass by in a flash and before we know what is happening we are forty, fifty, sixty...

—A Death In The Family (My Struggle #1), Karl Ove Knausgård

Sounds good, flakefly. I haven't read "Under the Surface" but I've read his "The Secret Ingredient" and it was excellent, I've no doubt another book of his would also be quality. It's interesting reading about how some of the role models in "Chess for Life" returned to the game after a break, like you, and thought of about how to approach it. Good luck with your training goals, either book sounds good to me.

I really loved this book. I think it's a very original piece and it adresses a topic which is generally left aside. I haven't read the full book yet, but I like the structure which is easy to navigate and some of the insights are really eye-opening. For example, I found the chapter on the Carlsbad structure one of best on this topic despite having already read a lot of them, including Sadler's own work in his QGD book. The way the GMs make their repertoire evolve over time is also very interesting, and shows that various approaches are possible, as long as they suit your skills and personality.