Lifetime Repertoires: The 10 Pitfalls to Avoid with Learning Openings on Chessable

Chessable can make your chess worse, not better

For a good 20 years, I found chess openings boring.

Then, in July 2021, I joined Chessable and became addicted for the next 12 months, working through dozens of opening courses.

Finally patching up one of my chronic weaknesses, I was ready to soar to new heights.

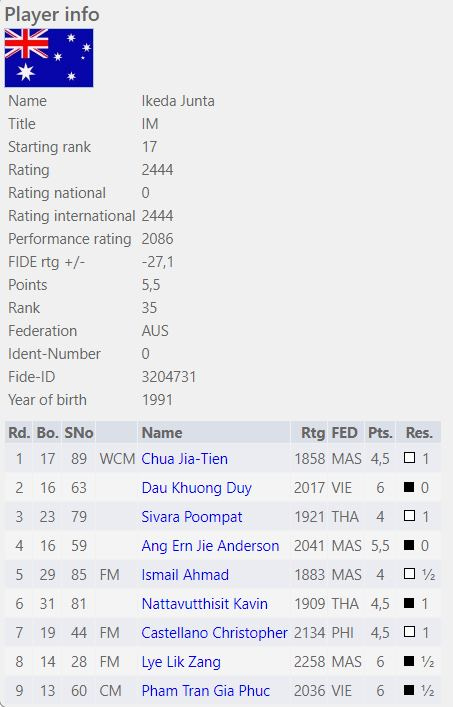

In October 2022, I played my first overseas tournament since 2018, in Thailand.

I had my worst performance in years.

My opening knowledge was incomparably better—but I’d gotten worse at chess.

I realised I’d:

wasted countless hours working on openings in the wrong way, and

neglected the other parts of my chess.

While I think Chessable is a great platform for learning, as with anything convenient, you have to be careful of how to use it or it could lead you astray.

Here are 10 lessons I learnt so you can avoid making the same mistakes.

1. Reviewing is overrated

Test your openings out in lots of games rather than spamming spaced repetition.

The most common lines and might-never-happen-in-your-life engine lines are weighted equally, so Reviewing isn’t very practical.

It’s better to see which lines come up the most from a) practice and b) the databases, so you can prioritise working on those through studying model games.

2. Understanding over memorisation

Let me tell you, you’ll be feeling like a human fingerfehler when you follow a Chessable variation to the very end of an author’s line in a game, and have absolutely no idea what to do.

Memorising opening moves doesn’t help you find better moves.

Understanding why you play each move, on the other hand, helps guide you even in unfamiliar situations.

3. Take Chessable offline

Spending all of your time on the website? It’s good to test how well you know your lines by creating a file from scratch, inputting everything you know. You’ll

identify gaps in your knowledge, and

find positions you’d like to explore further.

You can make these files in programs like ChessBase, or in Lichess studies. If you want to have the file ready-made so you can start browsing it immediately, Modern Chess is a good alternative as they provide the full PGN database.

4. Don’t spend too much time on openings

Many players spend too much of their time studying openings.

Sure, it might help you in your very next game as you reach a familiar position. It’s important to know the basic opening principles, and have some idea of what you’re doing.

However, being able to play good moves when you reach unfamiliar positions is much more important than investing your time and effort becoming an opening expert. Spend more of your time on the other areas by playing, analysing, solving and studying.

GM David Navara, in The Secret Ingredient:

I think the importance of openings is overestimated. Club players often say: “First, I need to build a decent repertoire of openings, then I’ll focus on middlegame and endgame.” To tell you the truth, you’ll never have a repertoire that you’ll be completely satisfied with. It’s a Sisyphean effort—there’s simply too much theory out there and it’s evolving all the time.

5. Have mix-up options for different opponents

The ‘problem’ with some Chessable courses is that they are for grandmasters to play against grandmasters. Objectively sound, solid, and strong. Which sounds good, until you’re playing someone you’re supposed to beat.

As Black, you might find yourself in an endgame as dry as your mouth when you’re talking to your crush for the first time as a teenager. You might also want to avoid particular choices against particular opponents, depending on their playing style or strengths.

So, have options. You might have different openings to play in different situations, or you can develop alternatives within the same system.

6. Fun doesn’t mean good

Gamifying can help with learning. On Chessable, you can gain XP for learning or reviewing variations, or earn gems for continuing daily streaks.

But at the end of the day, these XP and streaks don’t help you play chess any better.

You should be on Chessable when you’re sure it’s the best thing for your chess, not to extend some daily streak or achieve some daily XP quota.

7. Use Chessable as a reference, not a Bible

I used to

learn variations on Chessable,

play a game, and

compare what I played with what was recommended in the course, seeing the latter as best.

The problem with this approach is that you’re trusting the recommendations without questioning them at all. It’s a bit like mindlessly ‘regurgitating’ someone else’s chess philosophy. It’s good to use the author’s ideas as one of your sources, but rather than accepting it without question, interrogate it with curiosity, and compare their recommendations with alternatives from model games or the databases.

8. Get the order right

You see a new opening course published by a super-GM. You know it’s going to be amazing. You spend weeks learning it, and start testing it out in games. You’re playing the recommended moves, but somehow you never feel comfortable in the ensuing play.

Although it might depend a little on your level and experience, it’s important to think about which openings you want to learn, or might suit you first, before buying the course, rather than buying every new course on the block assuming it’s the one for you.

9. Don’t stop where the author stops

As in #2, you could be made to feel like an Accelerated Grob when the end of a Chessable variation is also the end of your knowledge. Where the author stops their analysis, you could say, is where you can get the most value out of exploring further yourself. The value in these courses shouldn’t only be in the variations, but the annotations which expand your chess knowledge and understanding by

showing you some treasures, and

helping you think about where else might be fun to dig.

10. The ‘Chessable era’

Chessable has an incredible library of opening courses, even by some of the world’s best players. There’s never been so many good resources available.

At the same time, it’s never been easier for your next opponent to also be booked up. Because the average level of opening knowledge is higher, it’s natural to think that you need to spend more time on openings, studying as many courses as possible.

I think it’s more exciting to think of it in another way—while it’s important to keep up with opening trends in a way which corresponds to your playing level, there’s never been a time when your pure chess strength, with all of its understanding, creativity and adaptability, can be relied on so much to bring you good results.

Because too many people are spending too much time following the latest Lifetime Repertoire.

Well said, Jim! I went through a phase where I wanted to copy all of the core variations from Chessable courses to my files in ChessBase, and I was way too greedy with how many courses I'd taken on over the months.

1. I wasn't smart enough to be more selective with courses, and

2. I let myself be tempted by quantity > quality, so my understanding of the moves was superficial.

I feel I had the exact mirror experience with chessable(even tough maybe it is because I am quite a bit weaker as a player, around 2200 fide). Similarly as the author, also for me openings were a weakness, and saw chessable as a way to put an end to this weakness. In a year I bought 3 lifetime's repertoires and completely changed my openings, learning variations by heart with spaced repetition (but clearly also trying to understand what I could).

The point is that the results form me were completely the opposite! After 10 months of this I did my best performance ever in a tournament achieving an IM norm. I think those chessable courses were an important part of that: in at least 3 games I overprepared IM level opposition, getting 1 draw and two wins as my opponents overpressed. So I really feel that against strong opponents Chessable repertoires transformed my results. But I agree that against lower/much lower rating opponents it is not such a great advantage. Especially with black, I already lost quite a bit of rating making dull draws in mainlines against 1900. So I ask, isn't maybe that bad tournament an exception due to poor form? Were those bad results repeated in time? Also, I think work with these repertoires lasts for long time, once variations are learned with spaced repetition one can slowly understand and assimilate them. Hopefully in the years to come you will be able to unleash all the power of the openings learned!