The Ultimate Guide to Defending Lost Positions in Chess

The weapons, tools and frameworks you can use to turn the game on its head

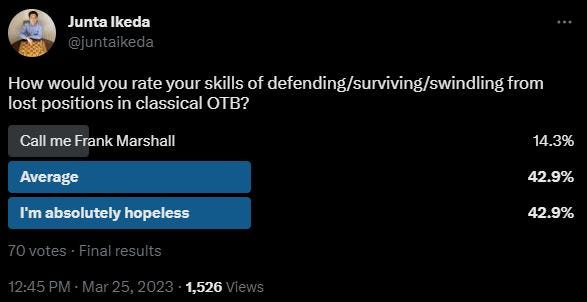

Do you know someone who keeps getting into lost positions, but somehow survives?

How do they do it?

Most people aren’t especially confident about defending.

GM Jan Markos wrote that defending is the most demanding part of chess in The Secret Ingredient:

not only do you need skills, but strength of character

you need to be both patient and able to take a risk

you need to devote a lot of energy to every move

you can never take an immediate reward for granted

it defies our human nature, which prefers activity to passivity and positive emotions to negative

if you need to defend, it means you made a mistake earlier. It’s hard to accept this and brace ourselves to play well.

So, how can you get better at this part of chess that even grandmasters struggle with?

You’ll be learning

the 4 weapons for defence

the 5 tools to swindle your opponent, and

the 5 frameworks to keep you motivated.

Markos’ 4 Weapons for Defence

Building a fortress is useful when the position is relatively blocked, and/or if you do not have many weaknesses.

Counterattacking is a better course of action when you have too many weaknesses.

Exchanging pieces might let you survive into a worse but defendable endgame where your opponent won’t be able to build much of an initiative.

Sabotage actions diffuse your opponent’s initiative before it gets dangerous. This can involve blocking important files and diagonals or pinning down potential attackers.

A defender who can employ all four types of defence, and recognize when to switch between them, will be extremely difficult to beat.

Markos’ weapons are useful to know.

But you already know: the mental side is what’s so hard with defending.

GM John Nunn wrote in Grandmaster Chess Move by Move,

It is easy to become despondent when the game has not gone as you had planned, and then there is a tendency to just ‘go through the motions’, look only at the most obvious lines, confirm that they are all bad and play one of them at random.

It is possible to train the mental side of your game.

To defend well, you need to learn about the psychology of defending:

how you can exploit your opponent’s potential vulnerabilities, and

how you can stay motivated, which are closely intertwined.

The best book for learning how to defend, or even better, how to swindle your opponents, is The Complete Chess Swindler by GM David Smerdon (available as paperback or on Kindle, Forward Chess or Chessable).

He suggests you go into ‘swindle mode’:

when you think you will almost certainly lose if the game continues the way it has been going.

Ask yourself these 3 questions:

What does my opponent want?

How do they plan to achieve it?

What’s good about my position?

Combining these three points, you can think about what the best practical approach might be to put a spanner in the works.

Smerdon highlights the importance of grit and optimism when defending, and shares the tools for exploiting different emotions your opponents are prone to feeling when they’re trying to finish you off.

Smerdon’s 5 Tools to Swindle Your Opponent

Trojan Horses, to exploit your opponent’s impatience. A deadly trap disguised as an offer of a shortcut to victory can be a big temptation for your opponent.

Decoy Traps, to exploit your opponent’s overconfidence. It’s a move that looks like it intends a rather simple, transparent trap, while the far deadlier trap—the true point—is concealed.

Berserk Attacks, to exploit your opponent’s fear. You’re lost anyway, so going for an all-out attack at least gives you chances to turn the tide. In practice, a sudden offensive often causes panic, especially if they don’t have much time left.

Window-Ledging, to exploit your opponent’s need for control. If the game proceeds with normal moves, the opponent has it easy. Take a risk and cause chaos, giving your opponent chances to go wrong.

Finally, Playing the Player. If you know someone’s chess style in detail, or have insights into how they respond to particular situations, you can play the moves that objectively aren’t best but maximise your practical chances.

Now we have the weapons and tools for defence.

How can we improve our mindset?

GM Jonathan Rowson, in The Seven Deadly Chess Sins, has a wealth of wisdom on maintaining your motivation while defending.

A lost position is not a hopeless position.

To retain your inner composure in a lost position, you need to forget the idea of losing and focus on the hope.

The Theory of Infinite Resistance, originally devised by Australian player, Bill Jordan. GM Ian Rogers:

It is a theory designed to encourage players to fully utilize the defensive resources available in a bad, or even strategically lost position. The theory postulates that when a player makes a serious mistake or reaches a bad position, if he or she continues to try to find the best possible moves thereafter he or she can put up virtually infinite resistance and should not lose…Of course some positions are beyond even perfect defence but their number is far smaller than imagined.

Rowson’s 5 Frameworks to Stay Motivated

The Goalkeeper’s Glory: It can be depressing when your aim is to ‘avoid losing’. Reframe it in your mind so you’re fighting to draw rather than lose, and your opponent is fighting to win rather than draw. The ‘winner’ is the player who gets their favoured result.

Cause Some Trouble: Play on your opponent’s fears. Most player are prone to getting attached to the idea of winning, so complicate things—active pieces and even vague threats help. Make them worry and lose confidence.

Keep the Third Result: No matter how bad your position, if you have even a remote chance of still winning, it can keep your opponent nervous and risk-averse. Don’t resign yourself to only managing a draw at best—when you’re only looking for options to survive, it’s easy to miss the golden chance to win.

Blackmail Technique: Most players want to win as quickly as possible. Giving them the option of going into an endgame which is technically winning but laborious can work wonders if they happen to dislike those scenarios.

What’s Good About My Position? Try to exaggerate the significance of the good aspects of your position in your own mind, and look for ways to impose these aspects on your opponent. Nunn and Smerdon also mentioned this so you can tell it’s an essential question for the defender.

Next time you see someone manage to hold or even win from a terrible position, or are studying such a game, think about which of Markos’ weapons or Smerdon’s tools they might have used.

Become familiar with those so you can use them when you’re in a losing position yourself. Remember Rowson’s frameworks to stay motivated and fight.

When you’re more comfortable with and become better at defending,

your results will improve, as you lose less often

even if you’re a bit worse, you’ll be confident that you can keep fighting

opponents will worry more if they know you won’t go down without a fight.

Tips from my own extensive experience of lost positions

When I know my position is objectively lost, I mentally write it off as a loss and tell myself, ‘I’ve lost this game, and that’s a shame—but I’m going to make it as difficult as possible for my opponent.’ From there on, any resistance you can put up, or any struggles your opponent encounters, are things you can be happy about.

Feeling sorry for yourself doesn’t help. What’s done is done—you have to focus on the present and how you can make things difficult for your opponent, even if it be threatening to make one small threat, or posing one last hurdle they have to overcome before the game’s truly over.

Fear is a massive element in chess. Fear of losing, fear of playing a bad move, fear of trusting your gut. No one is immune to fear. Even when things look hopeless, there are still chances to make your opponent also feel it—fear of missing a win, fear of letting you back into the game, fear of miscalculating. To reach your full potential in chess, you have to make an appointment at some point with your fears—including your fear of defending lost positions.

To defend oneself against a fear is simply to insure that one will, one day, be conquered by it; fears must be faced.

―James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

For another post on defending lost positions, check out:

The SLP Method - How to save lost chess positions? (ChessMood blog)

ChessMood even has a course on this topic—at the time of writing this (24/08/23), it looks like several episodes are unlocked even if you’re not a member so it’s worth checking out. You can also try your hand at the test exercises for free.

Awesome article! I typically just throw my pieces all around the board – sometimes close to the enemy king – and hope that by some miracle I find a checkmate. Thanks for all this great advice!

Nice article - quite a few points I hadn't heard of before. Also probably one of the toughest areas to train in one's chess game, because defending a tough position often involves a ton of small micro decisions - as opposed to finding one good move and problem solved, as you would have in most puzzles.