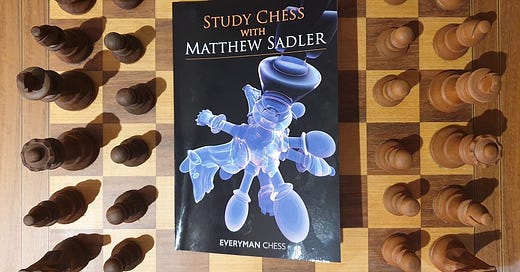

Book review: Study Chess with Matthew Sadler

★★★★☆ 4 out of 5 stars! 5 takeaways from the charming book

In this book I try to explain the most important skills for success as a practical chess player, and how you can train and develop these skills. In a nutshell, these skills are:

How to find new ideas in openings.

How to adopt new openings confidently and quickly.

The various ways of solving practical middlegame problems.

How to think in the endgame.

After enjoying Sadler (and Regan)’s Chess for Life, I was keen to read another book of his and found Study Chess with Matthew Sadler (2012). At just 140 pages, it’s pretty short and I devoured it in a couple of nights before re-reading my favourite parts.

Here are 5 useful insights/ways of thinking from the book:

1. Active vs. Reactive vs. Prophylactic thinking

The first and last types of thinking,

active (think about what you want and how to do it) and

prophylactic (think about what the opponent wants and prevent it)

are well-known but I hadn’t heard of the term ‘reactive’ thinking.

Reading Sadler’s definition, it sounds like using the method/process of elimination:

You turn your normal thinking on its head: instead of thinking what you want, you work out what can’t be done/what you don’t want and then just play/analyse what remains.

For example, in the game I covered in the previous post, there was this moment:

I want to get my king to c7

I want to get my Rh8 in play

I want to avoid allowing White to exchange their knight for my bishop

I was a little fixated on achieving the first two points asap so I missed moves like 22…h5 which would have been decent, but I saw that between a few candidates,

22…Kd7 or 22…Kd8 would allow 23.Ne5(+) followed by c4 snagging my bishop

22…f6 would allow 23.Ne3 Bc6 (23…Be4 didn’t feel right) 24.Nf5 when 24…Kf7 25.Nd6+ would end in a perpetual (I was wrong—there’s 25…Kg6 26.Rxe6 Bd7!)

so 22…Ke7 followed by moves like …Rd8, …f6 and …Kd7-c7 felt logical to me.

Using all three types of thinking is important in a game, and the way Sadler showed their pros, cons and characteristics through practical examples was illuminating.

2. How to discover new ideas in the opening

I liked how Sadler highlighted the difference between playing and analysing:

When you play a game you invoke all sorts of filters/prejudices (consciously or unconsciously) to reduce the amount of information you have to process. […] This is useful in a practical situation as it speeds up your decision-making process, but these filters can get in the way of the creativity you need in analysis. The goal in (opening) analysis is not to limit the game and make it manageable. The goal is to discover new truths, and those truths may well lie outside the boundaries of your prejudices.

Emphasising that he couldn’t use an engine to find ideas (only to check his ideas), Sadler introduced the six ‘mind-enlarging’ approaches he uses to leave his comfort zone and trigger his creativity when searching for ideas in the opening:

Disturbing the material balance.

You can’t do that! Not in this opening! Well, actually…

My goodness, you can play this for a win!

Crossover plans.

Acts of wanton aggression.

The spoilsport gambit (exchanging queens).

If you have no idea how to find your own ideas, and tend to just follow variations and ideas proposed in books or courses, this chapter will really open your eyes!

3. How to adopt new openings quickly and confidently, 1

Even if you ‘study’ a new opening seemingly thoroughly, when it comes to playing it, things can feel a bit off. You haven’t played enough serious games with it, and you don’t have that intuitive feel of how to play the typical middlegames that come up;

So I decided that an important part of my preparation time for a new opening should be dedicated to building up warm feelings about the opening.

“Jack-and-Jill thinking”

With openings you’ve played for years, you’ve played the moves and the ensuing middlegames so many times that you can explain the earlier moves with confidence.

That’s hard with a new opening you pick up, so Sadler recommends you think about what each move does in simple, concrete terms, e.g.

2…e6 (after 1.d4 d5 2.c4)

Reinforcing Black’s central presence on d5 and opening the f8-a3 diagonal to develop Black’s dark-squared bishop. Black is thus a move closer to castling. On the minus side, this move reduces the perspectives for active development for the light-squared bishop on c8.

I love this approach. Even if you know you should focus on understanding, you can’t help but sometimes mechanically memorise some of the moves in the early stages—so you might reach a tabiya without ever reflecting on the point of each move on the way. Thinking in this way (in preparation and over the board) helps you feel more comfortable with the opening itself as you’ve deliberated on the why of each move.

4. How to adopt new openings quickly and confidently, 2

Sadler’s tips on studying new openings through model games were also helpful. I touched on the topic in my post on model games, while he goes into more specifics.

For example, on his comeback to chess, he played a game with the Dutch Stonewall which he liked and decided to study the opening in detail.

He compiled instructive games, concentrating on famous names and good players he knew (Botvinnik, Bronstein, Spraggett, Yusupov)

From 150 games or so, he pruned it down to 80 of the ‘more interesting’ games which he then merged into one file in ChessBase

Every time he was playing through the games and saw a theme he liked, he flagged it in the notes ({!!}) and put a brief comment explaining the theme

“Since that first moment, I’ve played through this compilation maybe 10 or 15 times before games, adding a small comment here and there. It never fails to put me in a good mood for playing the Stonewall.”

Themes he picked out from Szabo–Botvinnik, Budapest 1952 and some others were:

Black didn’t mind exchanging off his dark-squared bishop.

Black developed his queenside with …b6, …Bb7 and …a5.

Black didn’t rush …c5. He only played it once he was completely ready.

Black expanded on the kingside with …f4.

White couldn’t find a way to get at Black’s position.

An instructive section for anyone interested in how to use model games.

5. How to think in endgames

Do you struggle with endgames? One reason they’re difficult is that the thinking required can differ from (openings and) middlegames and it can be hard to adjust mid-game. Sadler decided to always be conscious of the possibility of switching to an endgame by thinking about how the position would look with queens exchanged.

Aside from being mentally prepared for the endgame, other benefits he found were:

I was much more conscious of plans and possibilities to swap off to a better endgame.

I understood better when I started taking positional risks. At the moment that you start sacrificing your pawns or structure, you suddenly realize that you no longer have recourse to the endgame.

These are just a handful of the many fascinating topics that can be found in the book. Sadler has that knack for putting deep concepts into simple language with a friendly voice that makes you think, “hmm, this happens in my chess all the time, but I’ve never thought of it this way!’ Clearly, a sign of good writing from a wise teacher.

If you’re looking for a chess book that’s relatively short yet full of rich, practically useful takeaways, Study Chess with Matthew Sadler might be the one for you (also available on Chessable here).

I suppose you could call this book a collection of my personal ‘Eureka!’ experiences, those wonderful moments when something complicated suddenly feels as natural and as easy as breathing. Some of those insights needed a lot of hard work, and some only came after the sorrowful analysis of heart-rending defeats. Hopefully this book can spare you both the midnight oil and the traumas, and set you off on the right path from the very beginning!

P.S. I added pages to my Substack so now you can peruse my posts by category:

Nice review. I've only read Matthew's book 'Game Changer', but some of these other books you've reviewed of his sound quite interesting.

Very tempting to purchase. Are there lots of chess positions in this one that would require a board?