Long think

Is thinking for over 30 minutes in a game ever justified? What about 20 minutes? When do you consider spending 10 minutes ok?

Of course, it depends on the position.

Say in a standard classical game with a time control of 90+30, spending half an hour, a third of all your time, seems like too much unless it’s clearly in a critical moment that would decide the result of the game or have a significant impact on it.

You can spend more time on a move, for example:

the more time you have left;

the more important the decision;

the bigger the difference in objective or practical value between options;

the more likely it seems there won’t be many difficult decisions after this one.

Let’s have a look at the skill or ability itself, of thinking for a long time.

Very long think

Can you actually concentrate for 30 minutes over a position from a chess game, and use that time well?

Having clarity on what you want to achieve

Ordering your abstract and concrete thoughts

Cutting down on checking and rechecking variations…

Whether it be in a game or solving a difficult exercise, it’s a rare person who manages to achieve this, especially on a consistent basis. Such deep work is difficult.

That’s the thing about chess—in every game, countless skills and types of decisions are demanded from you, some you may not even realise unless you reflect on it deeply. For those who play classical games, it’s good to train both your fast tactics (more on this in another post) and more difficult calculation. Even for the latter, I’d usually commit to an answer after 15 or 20 minutes and compare with the solution. Often, when you’ve thought for that long, it’s easy to give up, thinking you’ve hit a wall.

I’d like you to try this exercise that I also tried last month. I’ll hand you over to my friend, GM Raymond Song who was one of the interviewees in a recent post—thanks Raymond for sharing this high-quality exercise with readers of this Substack!

Raymond: I've found that there is a lot of truth to the saying "long think, wrong think" during a chess game. Whenever you find yourself spending over 30 minutes on a move, it should be a big red flag that something is not quite right. You rarely need that long on a single move and if you catch yourself doing it, then probably you should just go with your gut instinct. I can give an example from my own game recently against a young IM at the Malaysian Open.

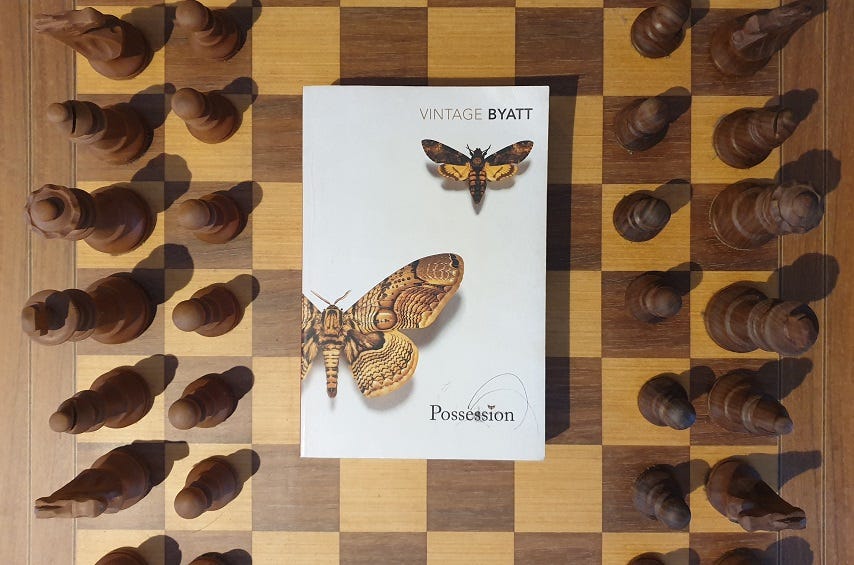

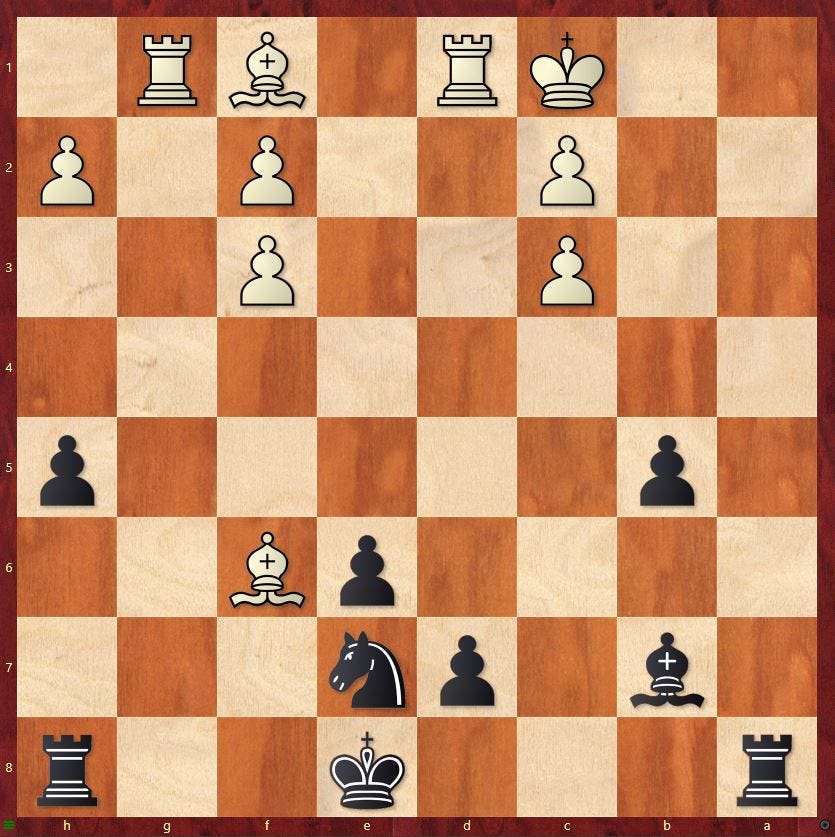

Poh Yu Tian (2377)–Raymond Song (2512), Malaysian Open (3), 29.08.2023

I was faced with this position shortly after the opening. Both of us were out of theory by this point, but I knew the objective evaluation was 0.00 since I had checked similar positions at home. The computer was always showing various ways for Black to completely dry out the game. So I knew it had to be fine, but as I started to think I realized that things were not so easy over the board. White has the pair of bishops, open lines for the rooks, and an extra pawn (!), all at the cost of a wretched pawn structure. As I started to calculate different lines, I started berating myself for not checking this line deeper (as it was very logical to reach this position given the line I played). As I sat there with a lot of negative thoughts, not finding a clear way to draw, my time ticked away. Eventually, after over 1 hour (huge red flag!) of thought, I made a faulty decision. I encourage readers to have a go first, before I post my thought process below. It's a great exercise to improve calculation and general chess understanding and perhaps you will do a better job than I did🙂

(Junta: please have a go if you feel up to a serious calculation exercise, writing down your variations and thinking of what the best move is on each turn for Black and White—I really suffered trying this one, so I want fellow victims. Your challenge is to focus on this position, no distractions, for 30 minutes (or longer if you wish). Write down your variations and thoughts, and compare with Raymond’s below! The exercise might be too difficult for some (I recommend to intermediate+), but it should be of interest to most players to have a go and compare. And for many of you, you might be reminded just how hard it is to simply try and concentrate on something for so long.)

Ready…go!

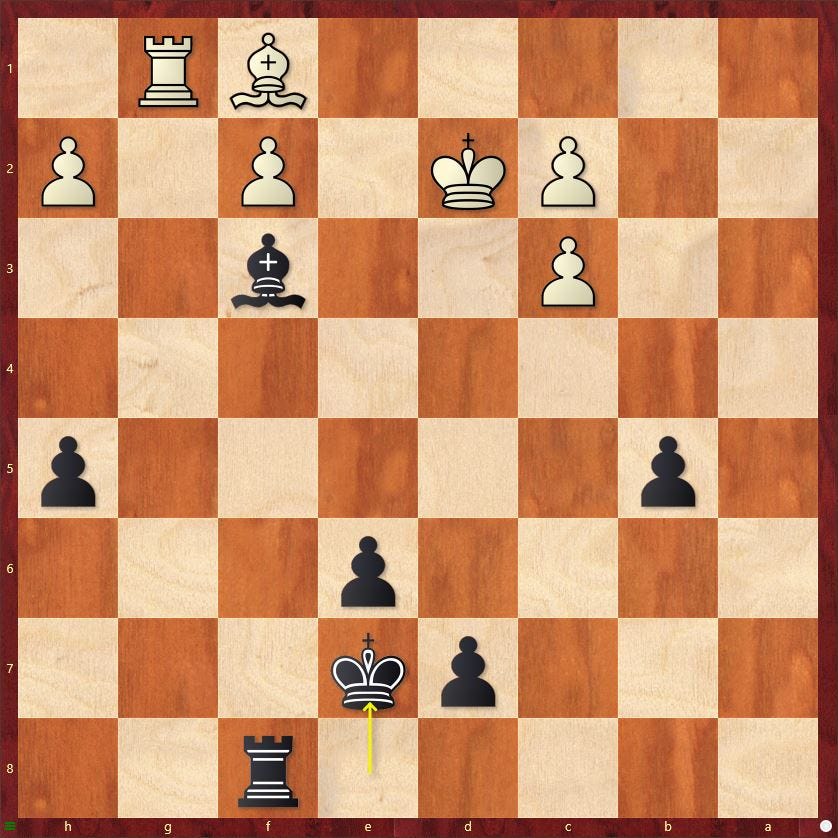

The first line I calculated was 1…Rf8 2.Bxe7 Ra1+ 3.Kd2 Rxd1+ 4.Kxd1 Bxf3+ 5.Kd2 Kxe7

This is the most direct line, and I could also get here starting with 1...Ra1+.

I felt that this had to be a draw with White's shattered pawn structure, but I understood I would be going down a pawn, so I started looking further:

6.Rg7+ Kd6 7.Bxb5 Bc6 8.Bxc6 Kxc6 9.Ke3

I stopped here, seeing f4/h4 followed by Rg5 coming for White and thought it was dangerous for me. What I had forgot about is that there is a simple way of generating sufficient counterplay by attacking White's pawns on both flanks: 9…Rf5! (not the only way but the easiest) 10.f4 Rc5 11.Kd3 Rf5, with a "perpetual" on the weak pawns.

As they say though, all rook endgames are drawn. While my gut was screaming at me to go here, I felt there had to be a "cleaner" way. So then I started looking at other options:

1...Rg8 crossed my mind briefly, but I didn't like that it wasn't direct. I saw that White could continue with 2.Rg3!? Rxg3 3.fxg3 Bxf3 4.Re1 for example, and with White's pair of bishops and 2v1 majority on the kingside, I felt it was dangerous.

Then I started checking 1...Bxf3, as it is a direct option and should be investigated. The first point is that 2.Rd3 can be met by 2…Rg8! 3.Rxg8 Nxg8 4.Rxf3 Ra1+ and Black draws easily.

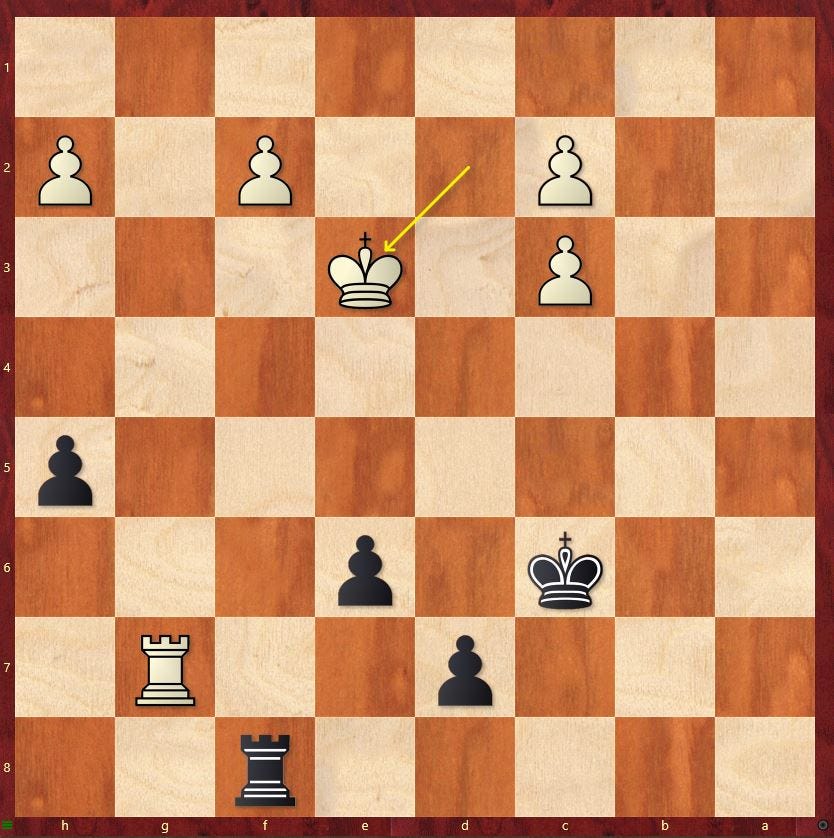

On 1...Bxf3, White's only critical option is therefore 2.Bxb5!

Here if we go down the forced path, 2...Bxd1 3.Bxh8 Be2! 4.c4! is an almost unbelievable resource

and the bishop from h8 covers the a1 square. This is not the end of the story, and during the game I had seen 4…Rc8 here should give me decent chances to draw, but after White replies 5.Rg5 I would be going down a pawn and again I wanted a "cleaner" way.

That’s when I had my most creative (and slightly insane) thought. Why not 1...Bxf3 2.Bxb5 Rh6!!!?? Now if 3.Rxd7 then 3…Rxf6, 4.Rgg7 Rf7 everything is protected. And instead of 3.Rxd7, if 3.Bg5 Bxd1 4.Bxh6 Be2! The White bishop is now on h6 instead of h8, and there is no more c4 resource covering the a1 square from h8! I understood that the whole thing looked suspicious, but I didn't see a concrete refutation, so finally after 1 hour+ thought and not liking the alternatives, I went for it.

Of course in chess if something looks suspicious, it usually is and you should probably trust your gut. I had missed an important detail in this line: 1...Bxf3 2.Bxb5 Rh6? 3.Bg5 Bxd1 4.Bxd7+! A nice intermediate shot and I'm basically lost. Kudos to my opponent for finding this line, as it is easy to miss from afar.

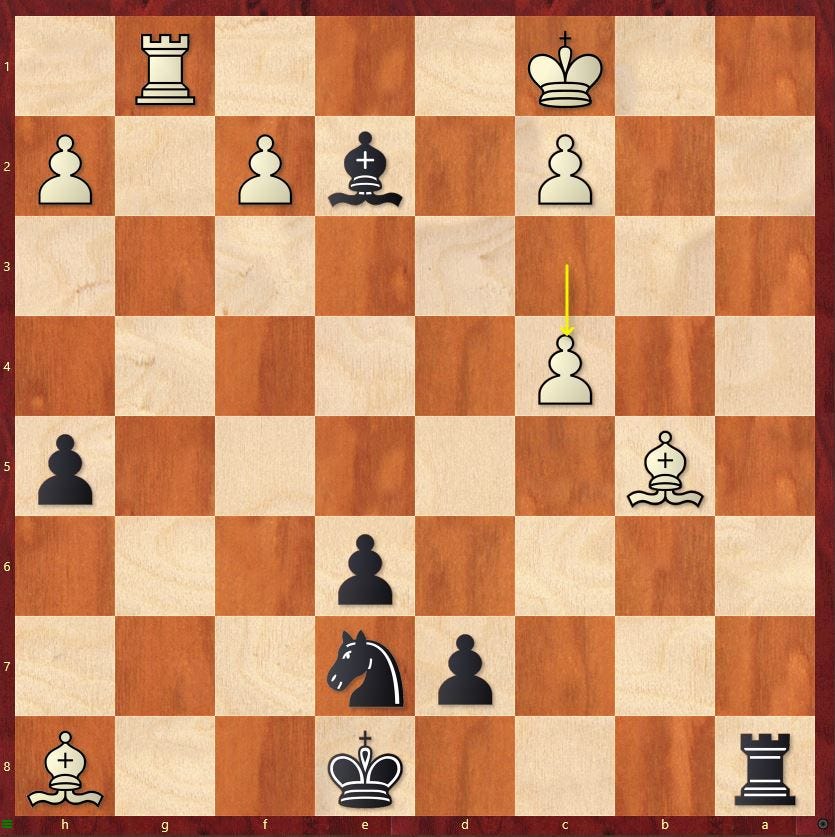

So, had I trusted my gut and followed the principle of going for rook endgames when defending due to their high drawish tendencies, I would have played 1...Rf8 2.Bxe7 Ra1+ 3.Kd2 Rxd1+ 4.Kxd1 Bxf3+ 5.Kd2 Kxe7 6.Rg7+ Kd6 7.Bxb5

This feels like a draw, and indeed the computer points out several ways, including 7...Bg4!? Rxd7+ Kc5 and Black will immediately regain the pawns.

Moral of the story: if you ever catch yourself spending over 30 minutes on a given move, identify the red flags and try to mitigate the damage!

I was just thinking it would be really interesting if you could interview Raymond about his return to chess after a long break, and his consequently quick climb to GM. I've always been curious about how he did it. I feel like there could be some interesting insights there.