5 Ways to Work on Your Chess

To complement spending some of your finite existence on this earth pushing wood

Getting better at chess is hard. Especially when you’ve been stuck around the same level for years, and you’re not sure what you should be focusing on.

It’s helpful to learn about approaches that successful chess players and coaches have recommended.

Let’s start with three frameworks from grandmasters whose writings on chess I respect a lot:

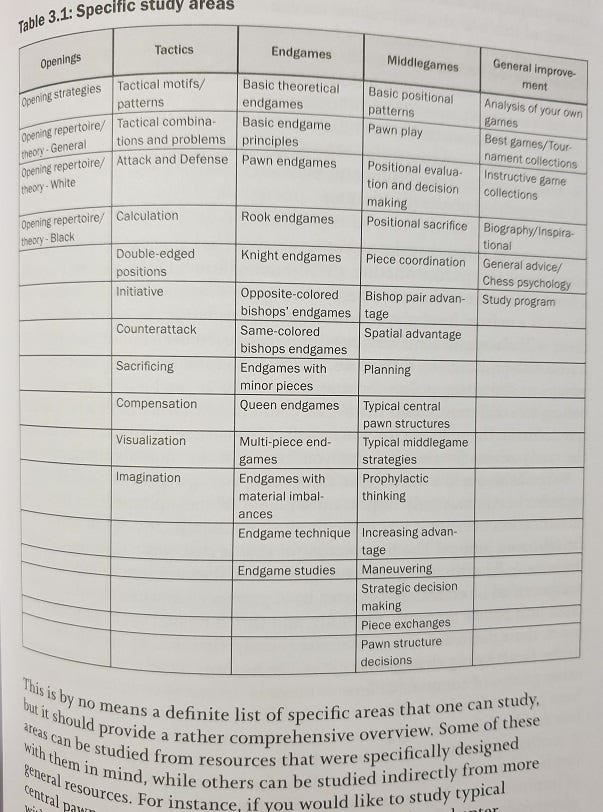

1. Distribute your time across 5 areas

In How To Study Chess On Your Own (the #1 book I’d recommend to serious players without a coach), GM Davorin Kuljasevic writes:

A reasonable approximation of general study distribution for an improving chess player would look something like this:

Openings: 10%

Tactics: 25%

Endgames: 25%

Middlegames: 20%

General Improvement1: 20%

In Chapter 9, Kuljasevic has a detailed guide on creating your own study plan.

2. The One-Third-Rule

In a blog post in January 2023, GM Noël Studer recommended chess improvers to split their training time equally on three areas:

Improving tactical vision and calculation

Playing and analysing your games

Openings, Endgames or Positional Chess, depending on your strengths and weaknesses

3. Study→Practice→Fix→Repeat

In another recent blog post, the founder and head coach of ChessMood, GM Avetik Grigoryan proposed the following formula for improving your chess:

You learn something first.

You practice it; otherwise, you’ll forget it.

You fix the mistakes you make.

Then you learn new things, and the cycle continues.

On how to know when to study and when to practice:

Ask, “Do I have anything to digest?”

If the answer is yes—time to practice.

If not, and you don’t have anything to “digest,” go back and study. Time to “eat.”

My thoughts on 1, 2 and 3

I like these approaches. Some key takeaways are:

Explore all of chess, but openings should be low priority (Kuljasevic)

Focus on the important areas, as well as what you need the most (Studer)

Don’t only think of which areas, but also whether to practice or study (Grigoryan)

I especially liked Grigoryan’s post as I had read some books on input and output in December. They also emphasised the importance of the cycle,

Input (learning)→Output (practice)→Feedback (fix the mistakes)→Repeat.

Here’s another observation by a Japanese Twitter friend:

Many people think about their training/study in terms of which areas, but it’s useful to ponder: “Do I have a good balance between study and practice?”

Too much study: you’re not consolidating what you’ve studied through practice

Too much practice: you’re neglecting expanding your horizons through study.

4. Take the long road

The three frameworks above simplify things and are useful.

While being conscious of your priorities, though, don’t feel guilty about spending time on the things you enjoy or are simply curious about.

Especially as adults, with limited time, we might think that the best approach is to get the most out of every hour we have by focusing on the most important areas.

Don’t forget about having fun.

It’s easy to spend hours in a concentrated state when we’re having fun, and spending a lot of time on something could help you develop some strengths or even something that distinguishes your chess style.

5. Receive feedback from others

One of the best things for improvement is good advice/guidance. Someone honing in on what we can do better or work on can save us a lot of time from trying to work it out for ourselves.

Play stronger opponents often so you can see where you might be lacking. If you’re only playing those you’re supposed to beat, you won’t be pushed to improve

When you lose a game, especially against a stronger player, ask them for their thoughts on where you could have played better. Engines can tell you where you went wrong, but your opponent’s perspective would be more practically relevant

Have a coach or training partner/s who can point you to where you could improve, and what resources or approaches are available to work on it

P.S.

If you’re serious about your chess, you want focused time on chess each day.

And an obstacle for many people there would be mindless scrolling/surfing on their phone/PC.

When I look at how much time I’ve spent on my phone in a day, and think about how I could have spent more of it on chess, reading or writing, I often feel like someone too trigger-happy to launch their flank pawns, neglecting development and castling.

Maybe you’re in the same boat.

Thank you for (mindful?) scrolling, and see you next time.

I’ll be reading your stuff with interest as you zeroed in on the only three sources for thinking about *how* to study chess, and this is after years of gravitating to such books. Also, I like your other posts. Welcome to Substack!