40 Good (Enough) Moves

Why it can be helpful to lower the bar from focusing on 'good' moves to 'good enough' moves

His credo was as follows: “I will make 40 good moves and if you are able to do the same, the game will end in a draw.” But it was precisely this ‘doing the same’ that was the most difficult: Smyslov’s technique was ahead of his time.

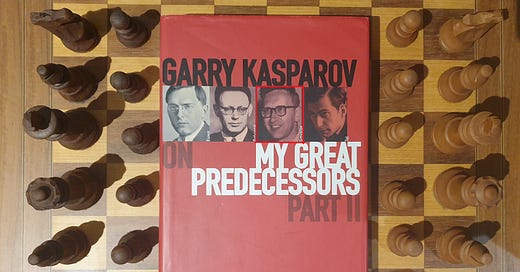

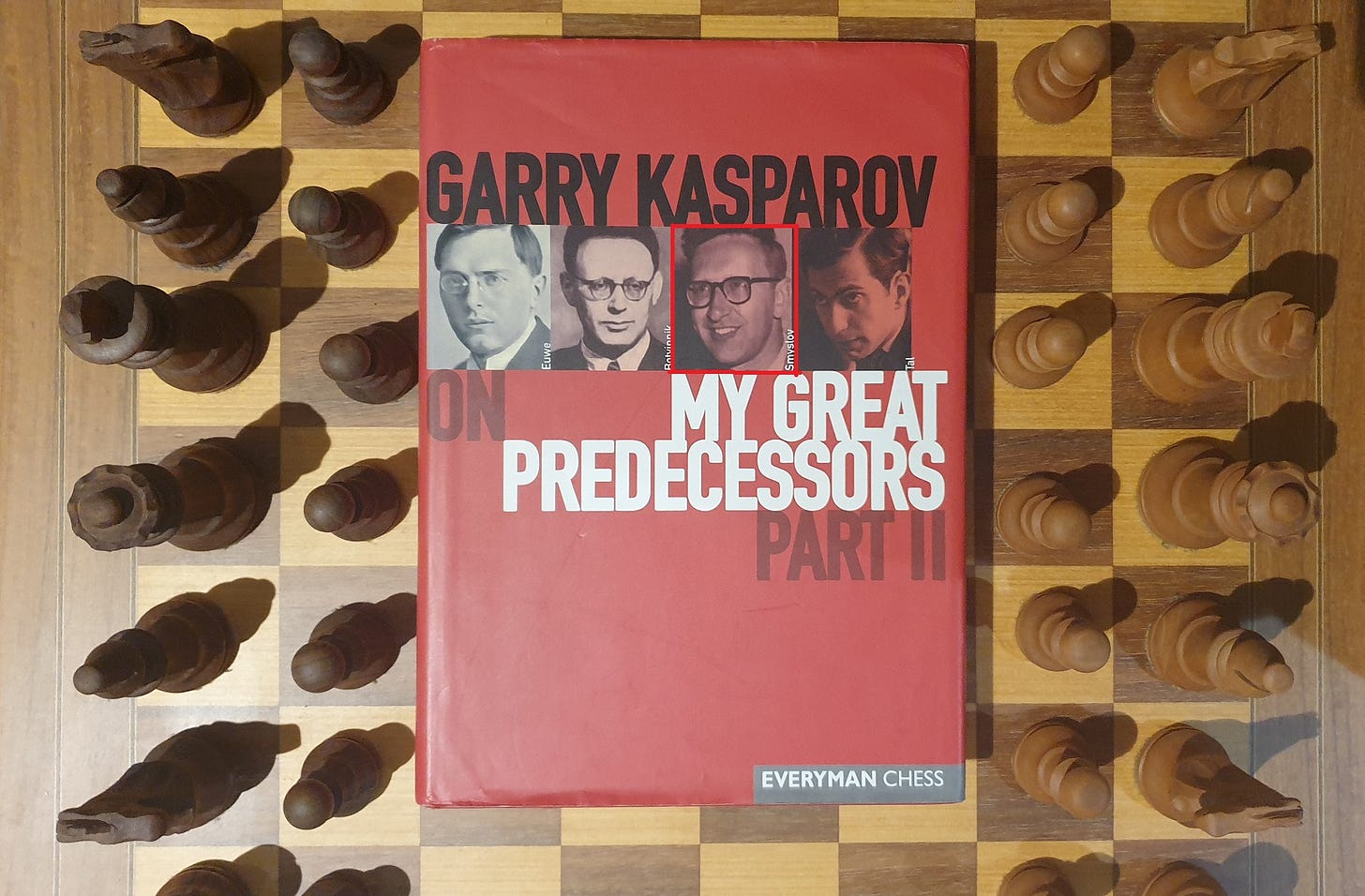

Kasparov on Smyslov in My Great Predecessors, Part II

It’s often more important to make good enough moves rather than good moves in chess.

In both cases, you’ve managed to avoid making a bad move. While good moves are clearly better than others, good enough moves might not necessarily be the strongest.

But they don’t worsen your chances, and keep the game going.

The difference between the two kinds of moves can be subtle but meaningful.

Here are three reasons why it pays to be mindful of making good enough moves:

1. It saves you from overthinking and worrying

From tactics to calculation exercises, a lot of your chess training is focused on finding good or even great moves, whether it be a forced win or the strongest move.

And indeed, this is a crucial skill to have in critical moments.

However, in many positions you have in a game, there is no winning best move, and you might have to decide between several options which seem to be equally strong.

This can result in:

spending too much time and energy trying to find the best move when there isn’t one

spending too much time deciding between several options when, practically speaking, it won’t affect the result of the game

blundering or making a mistake because you spent too much time earlier.

What you want to do in such positions is to lower the bar.

Don’t worry if you aren’t sure if your move is the best—you just want to make sure it’s good enough.

In many positions, it’s enough to make a good enough move that doesn’t worsen your position. Every move you pass on to the opponent is another position where they could slip up. Save your thinking time for the more critical moments, and work on

raising your floor: becoming better at avoiding bad moves, improving the level of your worst moves, rather than focusing only on

raising your ceiling: becoming better at making the strongest move, improving the level of your best moves.

2. It can win you games against lower-rated players

When do you realise you’ve gotten stronger at chess?

In my experience, it isn’t necessarily when you

notice that you’re finding more good moves than before, or

notice that you’re finding good moves easier than before.

Instead, you often find your opponents seem to make more bad moves than before.

You notice this because you can

sense better when they make a move that isn’t good, and

see better what the best way to take advantage of it is.

A corollary of this is that you might be outplayed by a higher-rated player not only because they make better moves more often than you, but because they make weaker moves less often. They don’t necessarily make the best moves, but they make good enough moves more often and don’t make as many moves that worsen their position.

I managed to win a local FIDE-rated tournament I played at the end of May, but the games were, as always, very tough. I out-rated the 2nd seed by >200 points, the 3rd by 300 and the 4th by >400—against these three players, it wasn’t that I outplayed them by playing more strong moves—it was more I managed to survive by playing good enough moves when it mattered (I’ve lost to two of these opponents before).

It made me think of this relationship between good, good enough and bad moves.

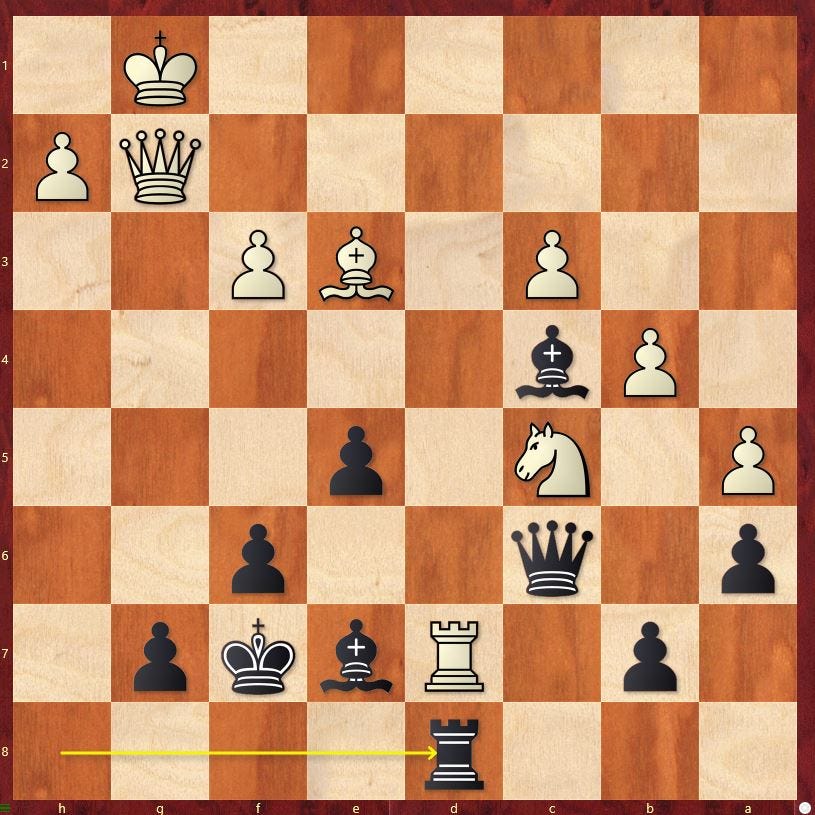

Round 4: vs. 3rd seed (2089)

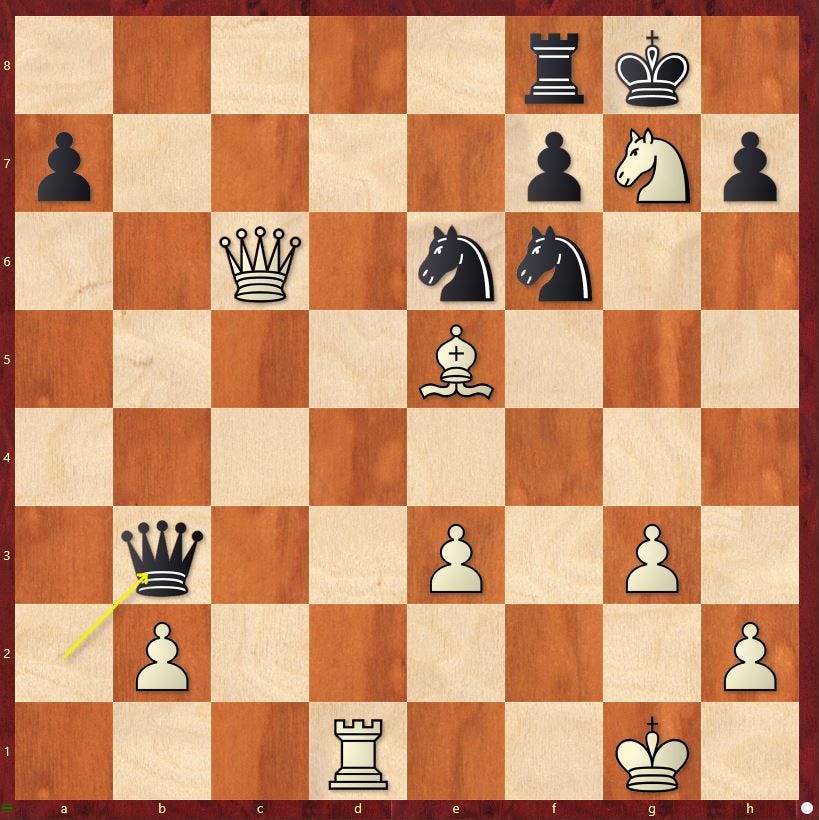

Round 5: vs. 2nd seed (2154)

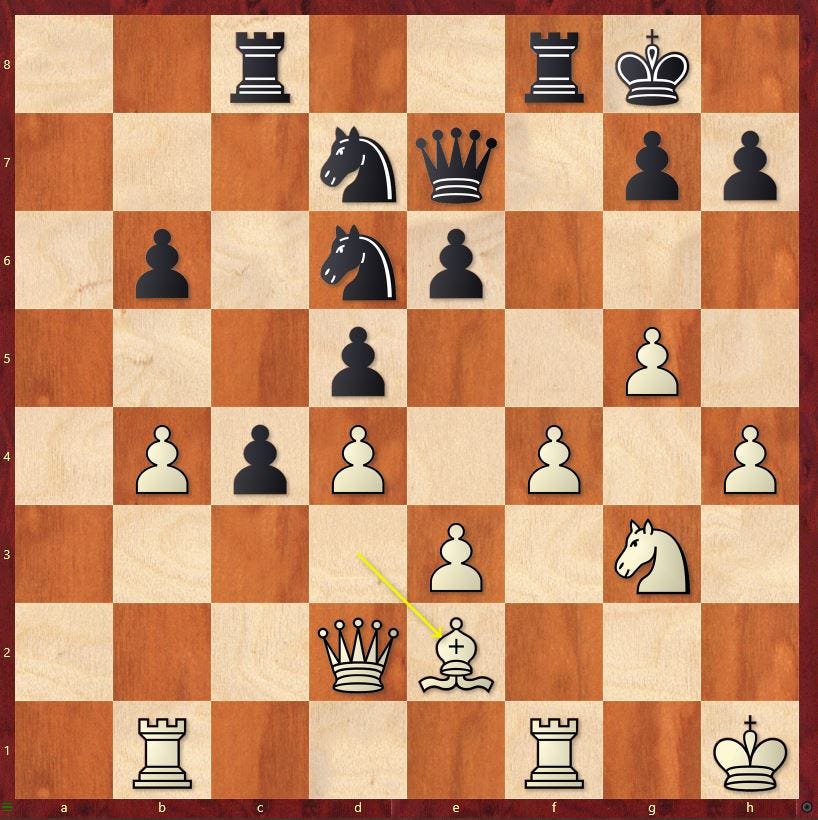

Round 6: vs. 4th seed (1963)

When you’re playing lower-rated opponents, there are games where you manage to play enough good moves and win—and others where you hang in there, playing good enough moves and hope your opponent makes a critical mistake before you do.

3. It can win you games against higher-rated players

In general, your higher-rated opponent will make more good moves and less bad moves than you. But in a single encounter, you have your chances if you play well.

You could cause a well-earned upset when one (or more) of these things happen:

you keep up with or even surpass the opponent in good moves and they make more bad moves than you when it matters

you keep up with or even surpass the opponent in good enough moves and they make more bad moves than you when it matters

you manage to avoid bad moves more than your opponent when it matters.

When you play a higher-rated opponent, it’s normal to feel intimidated. You might be happy with a draw in a better position. But remember—they have more to lose, and though they might not show it, they can also feel fear and anxiety like you. If it feels like too much to match them in good moves—fight them with good enough moves.

The main tip is believe in yourself. Play your moves and take no notice of the fact that the great master opposite you understands everything and has played great moves. Quite often they have not a clue and they’ve done something really stupid!

—GM Jon Speelman, Chess for Life

4. Summary and tips

In conclusion:

You tend to focus on finding and making good moves in your games but it’s also important to think about good enough moves.

Examine the differences between them in your own games. You might have spent more time than necessary on a particular move because you were fixated on finding a good move rather than a good enough move, or you might have made a mistake by playing a good enough move when the position required more.

Don’t avoid playing the moves you want to play because you’re scared they might be bad. Mistakes are inevitable. But incorporating playing more good enough moves into your play could help with making more good moves and less bad ones.

He was still too young to know that the heart's memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past.

—Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

This is brilliant stuff. Real food for thought.

Nice article, Junta. I like the part you mention early on about how this aspect of the game is a bit neglected by most conventional training (being very calculation heavy).

On a personal note - I think that this quick & simple decision making is something that I've definitely gotten better at compared to when I was around maybe 16 yrs old (and embarassingly a bit higher rated then). Had to override a lot of overly concrete tendencies that I developed from being a very tactically lopsided player.

Also look forward to seeing you down at the Gold Coast in a couple days!